Years ago, during a recapitulation of my life, I examined every memory I had of my relationship with my father. I looked at us fearlessly and was, at the end of my examination, finally at peace with Dad. My explanation of Dad as a father and as a man was loving but now seems almost clinical in its detachment as it documented his failures. Here is part of my examination:

Dad was an alcoholic. In my last conversation with Mom, a few weeks before her death, I asked her to tell me about their wedding day in 1935. Grandpa and Grandma Janssen had not approved of Dad, she said. “Why not?” I asked. “He had a bad reputation, I guess,” she said. She had moved out of her parents’ home because they disapproved of her going out with Dad and moved into her grandmother’s small room at the hospital where both worked. “You were pregnant with me,” I reminded her. She said they got married at Iowa Falls City Hall with strangers as witnesses. Mom was 20, Dad 30. “Where did you go that night,” I asked. “Well, I went back to the hospital.” “This was your wedding night,” I said. “Where was Dad?” “I don’t remember,” she said, “maybe he slept in his car.” “He was homeless!” I exclaimed. She was silent now, remembering that day. “How soon did his drinking become a problem,” I asked. “It was always a problem,” she answered.

Mom told a story about driving down an Iowa highway with married friends in the back seat. Dad, loaded, got angry with the couple, stopped the car in the middle of nowhere, and demanded the friends get out of the car. They did, and he drove off. “I was never so embarrassed in my life,” Mom concluded.

Dad loved sports. He owned a couple of DX gas stations during WWII and sponsored a softball team. I got to be the batboy, a roll I relished, proudly wearing my red and black polyester satin Stokes DX uniform. Later, though, Dad only rarely took me along on hunting and fishing trips, so I never learned the skills of those enterprises. He did join me in the front yard during my high school football days to throw passes to me. I would run straight out 20 yards, then cross to the right or left and Dad would unerringly hit me as I ran full speed. I dropped those perfect passes sometimes and I never forgot the time he said, “Butterfingers,” an appellation I wear to this day every time I fumble something.

I don’t remember Dad ever complimenting me rectly. Instead, periodically he would come home from work to say, “I saw Bill McKay today and I told him that you made the honor roll last semester.” Or, ”I told the boss today that you made first team football.”

Bill collectors called our house during my high school years, calls that my besieged mother had to field. Mom said that she was humiliated at having no money, having to beg Dad for grocery money. When I was 16 and working for the summer in a Canadian fishing resort run by a couple from my home town, the couple’s unpleasant little eight-year old boy told me “My parents say that your dad is a deadbeat.”

The next day, July 3, and the day before the resort’s biggest day of the season, a food truck stopped at our remote lake and I asked the driver if I could go back to International Falls with him. He said yes, so I hurriedly packed my bag, went into the resort kitchen and told the couple that I was quitting and going home. They were angry and shocked that I was leaving them in the lurch, shorthanded. I told them that their son had told me that they called my dad a deadbeat. I won’t work for you, I said. Angry, they paid me $60 for six weeks of 12-hour days without a day off, and I left. I told Mom why I quit when I got home. It never occurred to me to tell my dad. Toward the end of her life, I asked Mom if she had ever told Dad that story—how his son had had his back. Mom didn’t remember the incident.

Dad sold cars most of his life after he married Mom. When I was 14 and 15, beginning my driving days, Dad would sometimes come home from work and take me through his drinking ritual: he would hand me one of those iconic glass Coke bottles from the frig and tell me to “drink the top off,” meaning I was invited to chug the cold soda down to the first line in the bottle’s neck. Then he would say, “Take it down to the next line,” which meant I got another huge swig. Now, the bottle half gone after my two throat hits, he would fill the bottle to the brim with whiskey, put his thumb on the top, and turn it upside down to mix. Then off we would go, me behind the wheel of yet another exciting automobile that he had brought home from the lot. Maybe a new Packard. Maybe a used Cadillac that made me feel rich and privileged, no matter what our real financial reality was. Maybe tonight it was the huge torpedo of a Nash.

Out on the narrow two-lane Iowa highway with high curbs that could get you into trouble if you put a wheel over it, Dad seemed content in the passenger seat, drinking and enjoying the rural scenery. There was never much conversation, except for Dad saying, “Automobiles are the greatest invention in the history of the human race.” Whizzing along at 60 in a nifty car, I agreed with him completely. Then he would say, “Come on, put your foot into it. Let’s see what this thing will do.” This was the full curriculum of my driving instruction as I grew up, the self-taught skill of driving a car 100 miles per hour.

Three months out of high school, I told Mom that I would be staying with a friend for the weekend. Instead, I picked up my future wife at her college and we ran away to Montana, getting married along the way at 18 and 17. Later, in our first telephone call a week after our disappearance, Dad would say only, “Well, I guess there were quite a few things I didn’t know about,” an assessment that he could have plugged in at just about any point in our relationship.

A few years before he died at the age of 65, he was attending a neighbor’s party across the street from his house. I was visiting and happened to be in the front yard when Dad came out of the neighbor’s house. He didn’t see me across the street. I watched him trip on a low decorative fence along the sidewalk and fall down backward and hard onto the grass. He was drunk. I quickly went indoors before he saw me.

Before he died, Mom finally told Dad that she was through with him if he didn’t stop drinking, thirty some years into their marriage. He pretended to quit. After his funeral, I discovered bottles of vodka secreted all over the garage and in the back of the classic MG that he had meticulously restored.

In recent years, I have told my family and friends that I Identified with Jean Paul Sartre, the French existential philosopher, who said something like, “Thank god I didn’t have a father.” He meant that the absence of a father in his home allowed him to grow up free to learn and explore without the powerful imprint of a father, an imprint that would have shackled his ability to explore reality on his own.

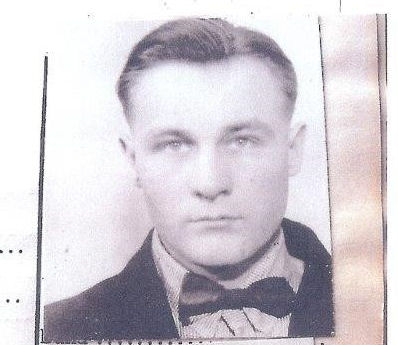

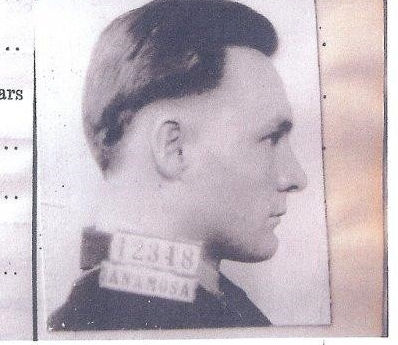

Now startling new information about Dad makes my earlier recapitulation seems like an inadequate explanation. My cousin, Carl, dropped by to share the results of his Stokes family search, including a photo of the ship that transported my grandfather, his 9 siblings, and his parents to Canada when they emigrated from England.

Carl saved up his most dramatic discovery for the end of his visit, reporting that my father, Compton, and his brother, Merlyn, had been convicted by a jury in their early 20s for larceny in the daytime and sentenced to five years in the penitentiary.

I knew nothing about this story, and I was skeptical. I had been close to the Stokes clan for decades while the generations ahead of me were still alive, and I had never heard anything about anybody in the family going to jail, let alone my own father. I had interviewed Mom at length about Dad in the year before her death. I didn’t get much new information in those interviews, just, “Oh, I feel so bad that your father didn’t give you more emotional support.” I have a drawer full of videotapes of those conversations, none of which has any hint about Dad’s conviction or imprisonment.

Carl didn’t have any documents with him to support his findings. I wasn’t disturbed by the possibility that Dad had been in the pen, but the unexplained past now had my full attention.

Carl has received documentation from the State of Iowa Department of Corrections. Dad, 23, and his brother Merlyn, 21, were convicted by a jury of larceny in the daytime of $57.79 and sentenced to 5 years each in separate prisons. Merlyn served 3 ½ years at Fort Madison Penitentiary. No record of how long Dad served. He entered Anamosa Men’s Reformatory on February 8, 1928, seven years before he would marry Helen Janssen, my mother.

- Four previous incarcerations—30 days, 30 days, 15 days, 10 days.

- Character of mother and father: good

- Conjugal relation of parents: Pleasant

- Former character: Fair

- Financial circumstances: Poor

- Moral susceptibility: Fair

- Character of associates: Fair

- Habits: Intemperate

Nobody in my large extended family had ever said a word about Compton and Merlyn being felons. My mother never revealed this secret, even when Dad was dead and I was asking her for details about his life. Dad never told me about this part of his life as a young man. He had told me that during WW II he—with two young children—had tried to enlist in the Army, Navy, and Air Force but was rejected. Was his prison record the reason?

Did he ever get to vote for his choice, Dewey, offsetting Mom’s vote for Truman?

Strangely, the reality of Dad’s life coming into sharper focus now, I am moved. I have been feeling a deep compassion for him. I do some more recapitulating. I remember Mom, Dad, Barbara, and me entering my grandparents’ home in Hampton, Iowa, on Christmas night, our annual holiday visit. Dad’s three brothers– Uncle Merlyn, by then a successful owner of a motel and trailer court that he had built with his own hands, Uncle Wayne, and Uncle Ray– would be there with their wives and my cousins.

Now I know that they all knew about Dad and Merlyn. The painful realities they had all shared were embedded in their relationships They all knew my father as a drinker with a criminal past. There must have been shame. Now I realize why they all seemed cautious and less than delighted when Compton showed up with his family.

I have developed a better explanation about Dad and me. I must have had it wrong about our relationship: In my original examination, I had been too aloof emotionally to have it right. I hadn’t acknowledged our connection adequately. I hadn’t been grateful enough to make a fair assessment. My recapitulation had been earnest rather than light-hearted. I was obviously not finished with Dad and me. The past is speaking to me assertively and I’m listening.

My saying I didn’t have a father was probably a combination of self-protection, judgment, and bravado. Yes, Dad, emotionally fenced off as he was and numbed to some degree by alcohol, could have been a much more engaged parent to me than he was. But I have incorrectly discounted his influence on me.

My life eventually turned out to be remarkably abundant, creative, and resilient. New research about ancestry (“How Your Ancestors Determine Your Social Status,” NY Times, February 23, 2014) reveals that upwardly mobile and successful lives are strongly influenced by inherited characteristics:

- The compulsion to strive

- The talent to prosper

- The ability to overcome failure

I have those qualities. I got them from my parents. I got them from Dad.

Dad was a model of striving. He moved from prison—homeless some of the time and jobless–to professional employment. He took risks, starting and running businesses. He moved from renting to home ownership. He got a real estate license at 62 and tried a new occupation.

He had enough talent to prosper, moving from penury to middle class life in Orange County, California, two cars in the garage, and all of the bills paid each month.

He overcame an immense failure. He had been in jail five times, the last time a crushing punishment for his inability to get things right with his fellow citizens. He emerged from defeat to marry a beautiful and accomplished pianist, raise two children who would be the first college graduates of the Stokes clan, and become a contributing member of community service clubs.

The past has called me back to revisit an incomplete examination. I did have a father and he was a guide to me, a positive influence as he passed down his compulsion to strive, the talent to prosper, and the ability to overcome failure. My recapitulation has been properly amended, and I see that I stand more than I have acknowledged

on my father’s shoulders.

I turn back to the present now, welcoming the future flowing in. My heart is filled with gratitude as I remember and honor my father, Compton Stokes.

Photo by Max Khokhlov

Beautiful!

Sometimes our thought are overmulched with things that we see as bad and we think the bad things made us become/grow stronger…the fact is ,there was a lesson,a divine influence which we would not see..

Wow, perspective really is everything. Thanks for sharing.

wow! Thanks, Gary.

I am at the age where I do a lot of reflecting on the relationship my father and i had. This puts a lot of things into perspective that I never considered before.

Thanks

Hi Gary,

It’s so compelling the impacts fathers have on our lives. Your title alone caused me to think of my own relationship with my father. I had been reflecting on my relationship with him just recently. So much so, that I finally wrote about it on my own blog. I’m grateful that my story is one of my father stepping up when it was most important to me.

Thank you for sharing your story. It truly helps us!

Hank

Thanks for sharing, Gary. You are a great story-teller. I really appreciate the fabulous balance in this post: you honestly acknowledge and accept the parts of your father and your upbringing that were not-so-marvelous, but then choose to focus on the parts that truly were good… and also have lasting positive impressions. True maturity, as far as I’m concerned. Thanks for your vulnerability in sharing your story with us all and inspiring us to undertake similar reflections on our key relationships. Very glad for you that you have found a peace with your father.

Thank you all for your positive comments about my post on Dad. I was not clear enough, or loving enough, at the end of Dad’s life to be able to tell him directly that I loved him. More clear and more loving, I could have thanked him for the strengths he passed on to me. What an exchange we might have had. Gary

Gary,

I can’t begin to tell you how moved I am by the recounting of your journey into understanding your father.

My story is with my mother. Last year, I spent time truly considering the woman she is today, all that she has endured, and all that she yearned for that has never come to pass. Before then I judged and condemned her behaviors. Now, I believe I understand her better and appreciate her more. It hope it has made me a better woman. I know it has helped our relationship. I’m sure your journey has made you a better man.

Thank you for your honesty and for sharing your journey and discoveries.